I've lately been reading quite a bit by and about the writer Zora Neale Hurston for a rather mad project I've embarked on, and reading this book was probably my deepest venture yet into the story of her life. I have also read Hurston's own account, Dust Tracks on the Road, which has its strengths, but this only takes us so far, as there are certain things Hurston would like to pass over--and have us pass over as well. Also, as with all autobiography, it ends before the story is over, and in this case, quite a bit before it is over, as Hurston was pressured by her publisher to attempt her memoir before she herself felt ready to do it. And still, we are lucky to have it.

One thing that seems very common to me is the struggle with vocation, with its companion theme of the struggle to discover one's material. I suppose there are people who have a kind of certitude about their gifts, but Hurston's relation to her own writerly gifts seems much more common. Her first desire was simply for education and to see some of the world. Few people who might happen upon this post will have faced anything like the kind of obstacles that lay before her. And with a gap of years in her life which she never spoke about, and which, to my knowledge, we have no remaining record of, we will probably never know all that she lived through before she became a writer and personality to be reckoned with.

As someone who lived at the center of the Harlem Renaissance, while at the same time attending the elite Barnard college, the first black woman to do so, it's understandable that she might have a little trouble fitting herself into typical roles. She tried to make the sensible decision of becoming an anthropologist and succeeded in this, though in an unconventional way. In this process, she added a lot to to what we know, both about African-American life in the American South of her era, and about that of the Bahamas, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. But though her books are an addition to our knowledge, a close reading of them reveals the stance of an artist and not a scientist. She doesn't always achieve the scientist's detached viewpoint, although I think her own 'semi-detached' viewpoint is instructive just in itself. I will hazard a guess that her anthropological works like Tell My Horse, and Of Men and Mules are really books by a novelist looking for her material. It's instructive, for instance, that it was while she ostensibly went on a trip to Haiti to understand the culture of voodoo, which, by the way, she treats with immense respect and becomes an initiate in, she also wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God--to my mind, one of the great American novels of the last century--in seven short weeks, apparently in her spare time.

The other aspect of her life that seems relevant to today's writers, and perhaps to writers at all times everywhere, is the utter contingency of her situation. Put more plainly, she was always scraping around for money--not because she lived an extravagant lifestyle, though she was generous with money, but because that is a writer's life, when not cushioned by a reliable job, a trust fund or something else more steady and predictable. She did try to find something like this--it's just that she never really managed it. There are some writers who can find or at least luck into one of these things, but I think the thing that struck me about Valerie Boyd's account is the idea that at root, Hurston's life is any artist's life. For the great majority of writers, and that doesn't by any means exclude the geniuses, there are plottings and negotiations, and maybe even a bit of kissing up, doing hack work and so on. People let you down. People have expectations that don't actually match up with what you are called to do. Even success doesn't provide future security. Hurston died in poverty. She was buried in an unmarked grave. (Which Alice Walker famously tracked down and bought a headstone for, so don't toss and turn at night about that part.)

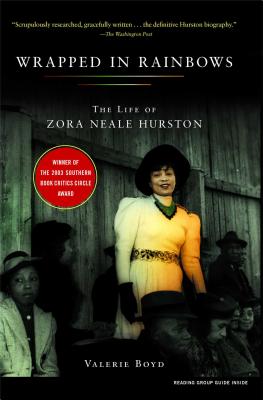

When you are keyed into a life, for whatever reason, the biographer of that life holds a special place in your heart. So I would like to take this opportunity to thank Valerie Boyd for her steady, calm, exhaustive and highly readable research into the life of a singular American author. I am sure that with such an extraodinary energy at the center of her field of enquiry, it wasn't always easy.